Change. It’s inevitable, constant. At times we don’t like change, but we deal with it. When writing novels, change is a necessary and valuable part of the writer’s toolkit. It makes characters, plot and settings more vibrant. This month we talk about change.

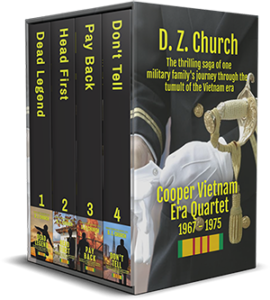

D. Z. Church

A Write to Change

When I start a series the first big question for me is … what is the main character’s past and how does it affect them as a person? Followed quickly by: Will the main character be an observer, unchanged by events or will they grow book after book? If so, how? Will there be a love interest, will a favorite protagonist or buddy become an antagonist later? Will the books occur only in the character’s main sphere of influence or will the character travel about … how far afield … how will the change of venue change them?

When I start a series the first big question for me is … what is the main character’s past and how does it affect them as a person? Followed quickly by: Will the main character be an observer, unchanged by events or will they grow book after book? If so, how? Will there be a love interest, will a favorite protagonist or buddy become an antagonist later? Will the books occur only in the character’s main sphere of influence or will the character travel about … how far afield … how will the change of venue change them?

Will the series have a stock set of characters that appear and reappear, will they grow and change? Does the main character struggle with right and wrong? Are they the sort of person willing to do what is necessary but not necessarily right to protect others? This prework defines the person at the helm of the story.

I’m going through all these growing pains with a new series that takes place in a small Illinois town starting in 1876. And have struggled with these questions, some answered before I began Unbecoming a Lady (out this spring) and others that have occurred as the series progressed to books 2 and 3. And, of course, I’ve had a few characters surprise me. The thing is, as you create characters, if they are real enough, they act like people, which means they may take an unanticipated action or point of view, changing in ways you hadn’t planned. To me, a sign that my story has taken wing is when the characters start changing right under my very fingers.

Just like we all change. We grow up, grow in vision and knowledge, and adjust our beliefs. Shouldn’t a character as well?

Some authors do this with ease, setting each book a few months or years after the last and moving the main characters along the continuum of time with concomitant changes. Some authors add main characters over the arc of their series and transition them into narrators, and so, enhance and bring change to the series. Some series and books have multiple main characters each telling their side of the tale as they muddle through discovering themselves while solving the mystery.

Many write mysteries in the first-person narrative, reporting only what the character observes. Those books act as comfort food to readers who know what to expect when they open the book, starting with the main character who is often perpetually the same age and living a life virtually without complications as they just do their job. They always solve the mystery in the end, no leftover weaselly serial killers stalking them or their loved ones, just brush their hands together, and get on with the next job.

I prefer mysteries/thrillers told in depth by interesting characters who show their emotions and who struggle and grow. As such, I tend to create protagonists with pasts that they may or may not be forced to overcome to resolve the story. Grieg Washburn and Calypso Swale in Saving Calypso, and Laury Cooper and LT Robin Haas over the arc of the Cooper Vietnam Era Quartet, who share every other book as lead, as they deal with the anger, ambivalence, and tragedy of the Vietnam War (in Vietnam and the U.S.).

I like series with characters that age, I like the years to pass, and gray hairs to appear. I like characters to fall in and out of love, to make stupid decisions with consequences. I like to read books written from multiple viewpoints and in the first person, and I like to write in both. Mostly I like characters that breathe, grow, and change.

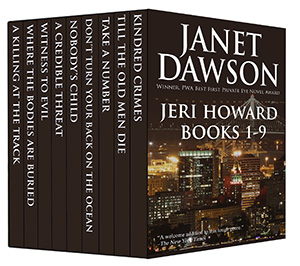

Janet Dawson

Things Change—So Do Characters

“My grandmother’s house is still there, but it isn’t the same.”

“My grandmother’s house is still there, but it isn’t the same.”

The song is “Secret Gardens,” written and sung by Judy Collins. When I hear it, I see a house in an old Oklahoma town, where some of the streets are paved with red bricks.

Grandma’s house, the site of many memories from my earliest days.

Sunday dinners with relatives grouped around the dining room table. Hot summers in the backyard, with uncles cranking the old wooden ice cream freezer. Christmas nights, bedded down with the other grandkids, unable to sleep because I was so excited about Santa Claus. Sitting on the floor in the dining room, playing with utensils taken from the kitchen, scene of creation for so many wonderful meals. And realizing I was growing taller because last year I couldn’t touch the latch at the top of Grandma’s china cabinet, and this year I could.

It’s been more than fifty years since Grandma died. The house is still there, but it isn’t the same. It looks smaller. It’s been remodeled on the outside, probably the inside, too. The garage is gone and so are the trees in the backyard.

But it’s more than physical appearance. The house has changed because Grandma isn’t there anymore.

When I create characters to populate my plots and settings, I want to make them believable, well-rounded, with virtues and faults, happiness and regrets—in short, people with real lives, not just stick figures moving around a stage like props.

My Oakland private investigator, Jeri Howard, has a back story and a character arc that has changed over the course of fourteen books. So does Jill McLeod, the sleuthing Zephyrette in my historical series set in the early 1950s. Both women have families and friends, and relationships galore.

Kindred Crimes is the first book in the Jeri Howard series. Her parents have divorced after decades of marriage, with her father, a history professor, staying in the Bay Area. Her mother initiated the divorce and has returned to her hometown of Monterey. Jeri gets along fine with her father, but not her mother. That tension is touched upon during the first three books in the series. I knew at some point I would have to send Jeri to Monterey to visit her mother. That happened in the fourth book, Don’t Turn Your Back on the Ocean, I had to send Jeri to Monterey to visit her mother. Fireworks ensue. Coming out on the other end, a gradual building of a better relationship.

In the first book, Jeri herself is recently divorced from an Oakland detective, Sid Vernon. In the scene where I introduce Sid, I make it clear that there are still some bad feelings after the divorce. But time and relationships move on. Jeri works with Sid to solve several cases, including one, A Credible Threat, when Sid’s daughter from his first marriage is threatened and we see Sid’s protective dad side.

Jeri also has relationships as the series progresses, first with a Navy officer, then a doctor. In Bit Player, she meets a travel writer and their relationship has grown and changed over the course of five books.

When we first meet Jill McLeod, in Death Rides the Zephyr, she is working as a train hostess, a Zephyrette. Her marriage plans were derailed when her fiancé was killed during the Korean War. So she went to work, riding the rails, and finds out she’s good at it. And what’s more, she likes it. During the first book, she meets a passenger named Mike and they begin a relationship, but neither of them are interested in something more permanent. At least not right now. Jill knows that, given the company rules and the times in which she’s living, she’d have to give up her job and career. And Mike, a veteran going to school on the GI Bill, would like get his degree and establish himself in his profession.

Characters who change from book to book—as a reader, that’s what I like. As a writer, that’s the experience I want to give my readers.

Janet Dawson

A Trip to Die For: Aboard the Amtrak California Zephyr, Bay Area to Denver

I board the train in Emeryville, California, the western terminus of the Amtrak route known as the California Zephyr. Since I write the historic Jill McLeod California Zephyr mysteries, I know that the Amtrak route is different from the one my sleuthing Zephyrette would take.

I board the train in Emeryville, California, the western terminus of the Amtrak route known as the California Zephyr. Since I write the historic Jill McLeod California Zephyr mysteries, I know that the Amtrak route is different from the one my sleuthing Zephyrette would take.

The original CZ traveled on Western Pacific tracks, down to Niles (now part of Fremont), then through Niles Canyon to Sunol, then up over Altamont Pass, stopping in Stockton before arriving in Sacramento. Then it went north to Oroville and up the scenic Feather River Canyon, to the small town of Portola, into Nevada at Gerlach and then stopping in Winnemucca.

The Amtrak route follows the old Southern Pacific route used by a train called the City of San Francisco, from the East Bay to Sacramento and then up over Donner Pass and down into Truckee and Reno before heading northeast to Winnemucca. This route is just as scenic, particularly in winter, with vistas looking out over the American River Canyon and high above Donner Lake. The train goes through snow sheds, built to protect the train from the elements.

Donner Lake and Donner Pass are named after the ill-fated Donner Party which was snowbound here during the winter of 1846-1947. You can find out more about this grim episode here.

This was also the scene of another blizzard on January 12, 1952, when 90-mile-per-hour gusts and snow drifts ranging from eight to ten feet stopped the City of San Francisco dead on the tracks, leaving 226 passengers and crew snowbound for three days. Read more about it here.

From Reno, the Amtrak CZ heads across the rugged terrain of Nevada, then over the Great Salt Lake Desert in northwestern Utah, into Salt Lake City. This portion of the journey takes place at night. In the second book in my Jill McLeod series, Death Deals a Hand, my sleuthing Zephyrette finds a body in one of the sleeper cars at night in the desert.

In southeastern Utah, the route of the CZ joins the Colorado River, running alongside the river for the next 240 miles. Glenwood Canyon, with its steep walls and rapids popular with rafters. Steep walls are ahead in Gore Canyon, where the river narrow and where Jill finds a body and confronts a killer in the first in the series, Death Rides the Zephyr. From here the train goes under the continental divide in the Moffatt Tunnel, then makes it way through other canyons, finally heading down the eastern slope of the Rocky Mountains at the Big Ten, a series of curves. Once on the high plains, the train gathers speed toward the Beaux-Arts Union Station in Denver.