Janet Dawson

Summer With Grandma

Ice cream. Wonderful creamy, smooth, sweet, delicious vanilla ice cream.

That’s what I think of when I recall those lazy summer days at Grandma’s house.

She lived in Purcell, a small town on the banks of the North Canadian River in central Oklahoma. Her one-story house on Adams Street had a swing on the wide front porch, and a deep lot with mimosa trees in the backyard. Grandma’s house holds so many memories—Christmas with a crowd of aunts, uncles and cousins; Sunday dinners with family gathered around the big table in the dining room; Grandma and her sister playing cutthroat Scrabble, both fiercely good players locked in combat.

When I think of summer, though, my first image involves ice cream.

Not ice cream out of a carton, mind you. None of that store-bought stuff, no way. I’m talking ice cream from an old-fashioned churn—the kind with a wooden bucket, a crank and a metal tube with metal paddles. Grandma made the mix, with cream, eggs and sugar, cooked on the stove until it was custard, then she filled the tube and put in the paddles. Ice and rock salt would be packed inside the bucket. Then my uncles would take turns cranking that paddle while I sucked on pieces of rock salt. Then finally, after all that work, ice cream! Sitting around the backyard eating that homemade ice cream and vying with my cousins to lick the paddles.

Then there was cobbler. Grandma made seriously good cobbler. With blackberries. Apricot was a close second. Now, the definition of cobbler changes from region to region. I refer you to a Bon Appetit article from 2019 that discusses the differences.

At Grandma’s house, cobbler was made in a deep square pan with a bottom crust filled with fruit, then a lattice crust on top. You might call it a pie, but not in my family. Anyway, once it’s baked, the crust nicely browned and the fruit bubbling between those lattices, then you can eat it plain, or garnish with ice cream or whipped cream. Another memory comes, and this one always makes me smile. It was way back when, and Grandma had never seen one of those newfangled cans that dispensed whipped cream. Suffice to say, the whipped cream shot straight up to the ceiling rather than onto the cobbler.

Which brings forth another summer memory. Watermelon. Heading out to the country with Dad and one or two of the uncles to pick out the best watermelon from a roadside stand. The seller would cut a plug out of the melon so we could sample to see how ripe and sweet the melon was. Then sitting outside eating watermelon and spitting out the seeds. Summer heaven.

Lest you think all my summer memories involve eating, they don’t. Well, maybe popcorn.

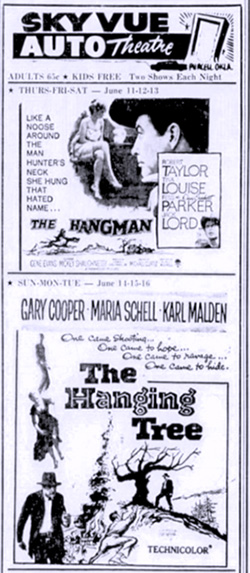

My uncle owned the movie theatre downtown, the Canadian, as well as the drive-in south of town, Sky-Vue. Remember drive-ins? When I was growing up, the cousins, me included, were at the movies all the time. After those big Sunday dinners, the grownups would send us downtown to the Canadian, where it was a big deal to take tickets or help my aunt sell popcorn in what she called the sweet shop.

In the summer, it was the drive-in. Sitting in a car with a speaker, listening to dialog and watching the movie through the windshield. But the best memory is going back to the projection booth to keep my uncle company, watching him lift huge reels onto the projector. He wore a sleeveless undershirt because it was hot back there, and he drank lots of carbonated water to stay hydrated.

Only then would I go to the sweet shop and load up on popcorn.

I hope your summer is full of memories.

D. Z. Church

Summers in a Fly-over State

I grew up in the Midwest. Back then, we lived on a street loaded with children. Most summer mornings, we met in the middle of the street to plan our days, including dips in whichever blow-up swimming pool was filled. We romped until our mothers called us in for dinner as dusk settled, and the soft breeze of the setting sun swept the heat from the day.

That’s when serious porch sitting took place. We’d gather outside the house, sit on the front stoop, and watch the sparkling fireflies rise and night fall. Once dark, my older sister and I would get in our shorty pajamas (mine had tiny pink rosebuds and a ruffle over the sleeves) and run barefoot to the stoop to say goodnight. Some nights, Dad would dangle the car keys for our giant aqua blue Nash, and we would pile into it for a trip to the Dairy Queen. My sister couldn’t lick an ice cream cone to save her life, even as an adult it ended up smeared across her face. I never had a problem; my tongue worked as fast as the cones melted.

During a short move to Maryland, we were introduced to swirl cones. Vanilla and chocolate ice cream swirled together. I love them, then and now. My sister would order a cup with her cone, stir it and eat it with a spoon. Why would anyone do that when the joy of a swirl cone is the two tastes melding in your mouth. Goodness sakes, just order a milkshake!

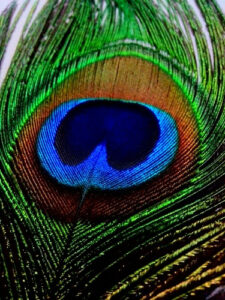

Best of all were summer nights on the family farm. As a toddler, I was installed in my grandparents’ bedroom, first in a crib, then in a twin bed beneath a window through which I could see the stars and hear the animals rustling through the night. Punctuated by the resident peacock’s horrifying warning of HELP, as Elmer, his given name, stood guard on the shed roof of the front porch.

After one sleepless night, my mother climbed out a window onto the porch roof, snuck up behind Elmer and flapped her arms. Elmer jumped and dropped to the front lawn. She thought she had gotten away with it until my grandfather waggled one of Elmer’s glorious tail feathers at her. Elmer’s tail feathers, with their magnificent eyes, were snatched, pulled and gathered so often by us farm kids that it was amazing he had any display at all for his peahens.

The milk truck rumbling down the lane to fetch cans of fresh milk announced the growing light, followed by the sound of cows padding down the drive and clopping across the macadam road to their field beyond, the chickens let out into the yard clucking, pigs snuffling, and the dogs barking. Oh my!

I draw on these memories as I write. So it happens that my characters inhabit summer nights evocative of a breeze lofting sheer curtains up and away from a sash window.

Though I admit, the newest Wanee Mystery, One Horse Too Many, featuring Cora Countryman, takes place in early winter when the first snowflakes glitter in the lamplight. Here’s a preview: Drugs stolen. The newspaper ransacked. Missing cash. What’s going on in Wanee?

One Horse Too Many is available for pre-order on September 1, with a release date of September 15.

Many summer nights, many picnics filled with great delight to you!

A Lovely Place to Die: Lincoln, NM—The Most Dangerous Street in America

In 1878, President Rutherford B. Hayes called it “the most dangerous street in America.” He was talking about the street that wound through the small village of Lincoln in New Mexico territory. Hayes had just appointed Lew Wallace as territorial governor. Yes, that Lew Wallace, the guy who wrote a novel called Ben-Hur.

Wallace was there to untangle the violent conflict known as the Lincoln County War. Dozens of books have been written about the war and its participants. The most famous of these was a young man who called himself Billy Bonney. Everyone soon knew him as Billy the Kid.

The short version: the war was a dispute over economic and political power. Two factions faced off, the established contingent led by merchants Lawrence Murphy and Jimmy Dolan, the upstart challengers led by Englishman John Tunstall, lawyer Alexander McSween, and famed cattleman John Chisum. Things went from bad to worse. Tunstall was murdered in February 1878, a killing that resonated all the way to London and had the British ambassador in Washington DC demanding answers. Among Tunstall’s supporters were the men who’d worked on the Englishman’s ranch, including Billy the Kid. Legend has it the Kid vowed to kill those responsible for Tunstall’s murder.

The dispute escalated into more violence, with a pitched battle that raged for five days in the tiny village of Lincoln in July 1878. That left McSween and others on both sides dead. Bitterness and anger lingered, boiling just below the surface, leading to more killings in the following months.

That’s when Wallace came on the scene, trying to bring peace to the restive county. He declared an amnesty and sought information. That brought him in contact, through correspondence and ultimately a face-to-face meeting, with Billy the Kid.

The whole town of Lincoln is a New Mexico state historical monument, and you can see facsimiles of Billy’s letters to the governor in the visitors’ center. All along the street are buildings full of historical significance, including a round structure called the Torreon, a tower built in the 1850s, where the Hispanic farmers who founded the village sheltered during attacks from the indigenous Mescalero Apache. To the west is the store that was owned by Tunstall and McSween. The McSween house next door is gone, burned to the ground on the last night of the battle. McSween and Tunstall are both buried behind the store, and visitors leave coins on their graves.

Farther west is the Wortley Hotel, now a bed and breakfast, where I stayed during my recent research trip. Across the street is the old Murphy store. After the war, it became the courthouse. And a jail, where Billy the Kid, captured by Sheriff Pat Garrett in December 1880, awaited hanging for killing Sheriff William Brady in the months after Tunstall’s murder. Billy was guarded by two deputies who had been in the Murphy faction, John Bell and Bob Olinger.

Billy had no intention of keeping his date with the hangman. In April 1881, Olinger left his double-barreled shotgun in the upstairs armory and went across the street to the Wortley Hotel for his midday meal. Despite being cuffed and in leg irons, Billy managed to get hold of a revolver—there are different stories as to how. He killed Bell and got into the armory, where he grabbed Olinger’s shotgun. Upon hearing the shot, Olinger ran across the street. Billy was at an upstairs window with Olinger’s shotgun. He said, “Hello, Bob.” Then he fired.

As the wary citizens of Lincoln watched, Billy got free of his shackles, stole a horse, and rode out of town. Of course, the odds—and Pat Garrett—caught up with Billy three months later in Fort Sumner when he was tracked down and killed by Garrett. But that’s another location, and another story.